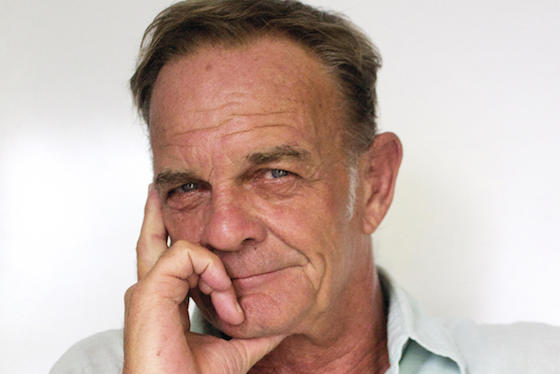

Sailor turned architect turned hotelier Fredo Taffin talks about his journey to millennial-oriented resort brand, Le Pirate. This is the latest in a series of profiles of leaders around the world challenging the status quo. Read them all in HOTELS’ April issue.

Fredo Taffin sails to the beat of his own ship. In just several years, the French-born architect and hotelier created Le Pirate Beach Club, a group of branded Indonesian resorts with a dedicated millennial following. But the journey was a roundabout one.

Taffin’s path started, not in hotelier school, but on the sun soaked deck of a yacht. Back in 1976, he was 19 and had just finished studying architecture. Rather than jumping into a desk job, he became a sailor, captaining a handful of yachts and ultimately designing and constructing those same yachts.

It was when he settled in Bali in 1985 that his life started to shift toward hospitality. He first tried his hand at designing villas for Bali expats, ultimately opening his own beach club hotel on the Indonesian island of Nusa Lembongan.

“I was probably a little bit ahead of the times,” Taffin says. “I struggled at the beginning to make the resort and cruises successful because I had to do all the hard marketing work of launching a destination and a package in an immature destination.”

That immature destination would ripen over the next decade, and in 2013, by the time Taffin opened the first Le Pirate on the neighboring island of Nusa Ceningan, Bali had become more of a destination for Australians and Brits, who make up a large percentage of Le Pirate’s clientele.

Le Pirate’s concept caught the eye of Horwath HTL’s Robert Hecker two years ago at a conference in conference in Jakarta.

“I thought his product and concept was the perfect solution for developing resorts in more remote locations where construction from scratch can be difficult, time consuming and expensive, and where intrepid travellers want to go, but otherwise have no or limited quality accommodations,” Hecker says.

The concept in the early days wasn’t perfect. Initially, service was sparse and food was basic buffet style meals served daily. All that changed after Taffin brought on his son, 26-year-old Louka Taffin, as head of Le Pirate’s marketing. Tapping directly into guest response, the younger Taffin revamped the F&B, switching over to an a la carte menu that’s now standardized at all three existing Le Pirates. Linen changes and housekeeping became daily and Le Pirate adjusted the prices on its bike rentals after guests complained that they weren’t competitive with local rates.

“For us, when it comes to marketing – yes, you can focus on the pretty pictures and what people see, but the most important thing is the guest experience, because at the end of the day, they’re going to be the ambassadors of your brand,” says Louka Taffin.

Those ambassadors dominate Le Pirate’s Instagram account, which has over 50,000 followers and only posts photos tagged by guests. Along with word of mouth, the social media site drives the brand’s foot traffic – amounting to some 29%.

Occupancy consistency is currently such that Le Pirate operates almost 100% sans OTAs. (They still use booking.com, but hope to eliminate that as well by 2018). In terms of expansion, Fredo Taffin says he’s been in talks with potential partners in Sri Lanka and the Philippines, with the goal being to open six more Le Pirates and two small-scale cruises in Indonesia over the next five years.

Part of the brand’s success also relies on a low-density, low-cost model. Each Le Pirate is small (the original has just 10 keys, the other two have 24, 14), and average cost per key for the three resorts is about US$40,000, with upfront investment averaging around US$700,000. An average night’s stay at a Le Pirate clocks in at about US$60, meaning guests can direct cash at other amenities like rentable bicycles and paddleboards and, in the case of Le Pirate Labuan Bajo, a boat excursion packaged with meals and snorkeling.

Taffin’s advice to more the more established hotelier world is flexibility – finding that balance between what defines you as a brand while not being afraid of handing over power to guests.

“Very often, traditional hoteliers are contained by overheads and systems and it’s very hard for them to reform,” he says. “We started in the market we wanted, so we have shaped our systems based on this market.”

Taffin’s son Louka agrees. “Try to create a rougher edge, where it’s a little more authentic and based around experiences and activities,” he says. “Millennials don’t care as much about the rooms anymore, it’s about what the hotel has to offer.”